Lavender Consciousness: Queering the Black Family Through Letters to God

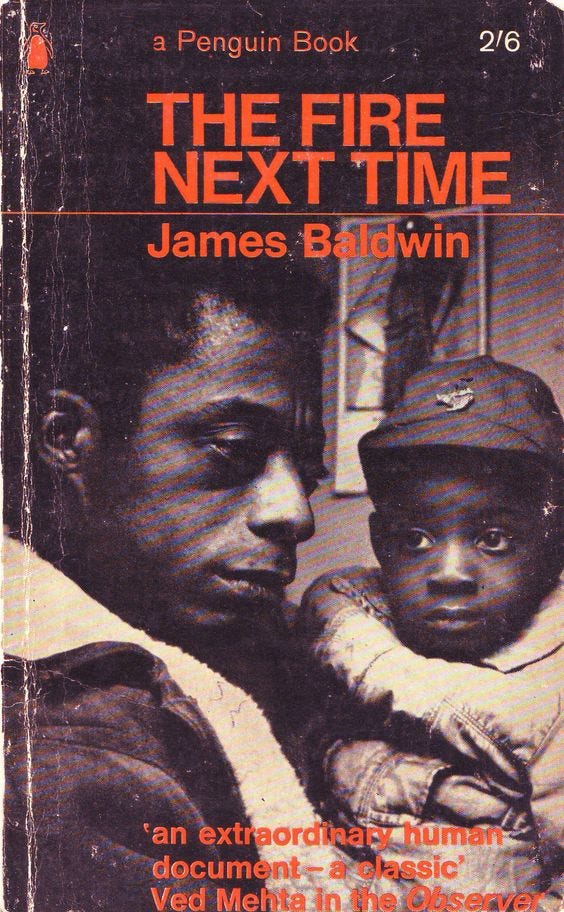

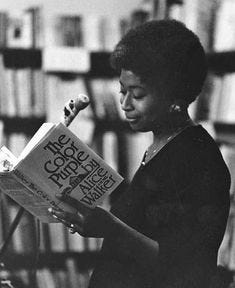

An analysis of the Color Purple by Alice Walker & The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin. Mild spoilers!

There is a radical queer philosophy of love in Epistolary and Black Jeremiad forms of African American literature. The narrative form of letters to god is a tradition among Black storytellers to weave together intimate and personal family narratives with political ideology. Alice Walker’s The Color Purple and James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time exemplify the use of epistolary form to articulate a queer reimagining of the Black family structure centering around an ethic of love. In letters to god, both Baldwin and Walker present a spiritually queer consciousness.

In Walker's novel, the protagonist and narrator Celie transforms her family. They suffer, hurt each other, forgive, and find god. Creating a queer family from abusive roots. The Fire Next Time, is a pair of letters from James Baldwin to his nephew. It shows a Black family's love beyond the binary of a nuclear family. Baldwin's novel encapsulates how familial love is empowering especially for oppressed people. Baldwin describes an unshakable authority that comes with self-love, then the empowerment of that authority when inherited. He uses the epistolary form to create a story of Black ancestry. Love is a political tool to wield.

The final line of poetry from Baldwin’s first letter reads. “The very time I thought I was lost/ My dungeon shook and my chains fell off” (Baldwin, 1998). Celie was trapped in this metaphorical dungeon lost within herself. And through her wonderings to god, her dungeon shook, and by the end of the novel, her chains were broken. As she transformed and began to live for love, so did her family. The key to not drowning in suffering is to reorient how we love each other. Baldwin through this novel is telling his nephew how much he loves him, how much the world is changing, and to not let the world distort how you love yourself. Celie is also reckoning with these same sentiments. Both Baldwin and Celie are queering the black family structure to actualize love on their terms.

WEB DuBois in The Souls of Black Folk provides a poetic case study on how Black Americans are racially socialized. The self is the result of a series of social processes such as mutual recognition and communication. From a sociologist's perspective, DuBois investigates the development of self that happens when a person is oppressed. Racialization distorts a Black person's sense of self. He articulates in prose the concept of race as a social construct. This double consciousness or invisibility is something that the epistolary form speaks directly to. The personal narrative to god humanizes the speaker immediately. It creates vulnerability and secrecy between the reader and speaker. Intimate to the point you can not ignore the writer's proclamations of humanity. Proclamations for understanding, and the listening ear of an omniscient god.

God sees the speaker when no one else will. The Black jeremiad within God's jurisdiction holds the white power structure in contempt for hypocrisy. Political thought derived from the personal narrative is the essence of both Baldwins and Walker's work. The impassioned political essay rooted in religious morality has transformed into a canon of Black literature. The personal oratory speech in god’s name advocating for Black liberation is transformed into a queer letter to god. The meshing of epistolary and Black Jeremiad traditions exemplifies a new ethic toward Black liberation.

The opening sentence of Walker’s The Color Purple reads. “You better not tell nobody but God. It’d kill your mammy” (p. 1). This beginning sentence of narration incites a lot of shame. The speaker's spirituality is rooted in sinfulness. This epistolary is a confession to an angry higher-up. A deviant is pleading for refuge from hell. What is this wrongness eating up Celie's soul? Why must she grovel to this flawed image of god?

In 1983 Walker published a collection of womanist (I recognize her history of transphobia, and that can be elaborated on in a second essay) prose entitled In Search of Our Mothers Gardens, to record the history of Black female artists that have been erased. She described these magical ancestors saying.

“They stumbled blindly through their lives: creatures so abused and mutilated in body, so dimmed and confused by pain, that they considered themselves unworthy even of hope. In the selfless abstractions their bodies became to the men who used them, they became more than “sexual objects,” more even than mere women: they became “Saints.” Instead of being perceived as whole persons, their bodies became shrines: what was thought to be their minds became temples suitable for worship. These crazy Saints stared out at the world, wildly, like lunatics—or quietly, like suicides; and the “God” that was in their gaze was as mute as a great stone” (p. 337).

In part 4 of In Search of Our Mothers Gardens Walker describes The Color Purple as a historical novel about two women who feel like they are married to the same man. I would assert that the novel is about that, and also two men in love with the same woman, and so much more. Celie and Shug are both beyond the gender binary. The narration shines Shug in masculine light anytime she exposes her strong will. The queerness of their love lies in its mutuality. In a culture of dominion radical love is biting. This political sword is how Celie can transform from someone motivated by ritualist shame to a person capable of breaking the gender binary to heal her family. The perspective Walker chooses to paint Celie's story in is a brandish of queer political praxis.

Baldwin asserts in his novel “I do not mean to be sentimental about suffering– but people who cannot suffer never grow up, can never discover who they are'' (Baldwin, 1998). It took me reading Celie's story through Baldwin's eyes and then listening to bell hooks in response to Baldwin say “Growing up is, at heart, the process of learning to take responsibility for whatever happens in your life. To choose growth is to embrace a love that heals'' (p. 210). To understand that the queer part of this journey is the truth and reconciliation part. The same place of despair and burning shame Celie is coming from in this first sentence is the same place she loves and sees lavender in by the end of the novel. We get there through an ethic of love.

DuBois describes the emotional, spiritual, and historical dissonance descendants of enslaved Africans feel in the US. The position of a dark-skinned able-bodied female slave during the antebellum period is a distorted manifestation of the Cult of True Womanhood and Victorian morality. The female slave within a cult of domesticity is empowered by upholding obedience and purity on the behalf of her master/husband. Gendered spheres of influence such as women being the domestic private facing front of the household and men being the public face is a tenant of Victorian morality that is embedded in Black Christian theology.

Baldwin, like many others, first and most influential cultural images of family, religion, and love began in the Black church. The shame of our adulthood is informed by the perceived sins of our childhood. Leaving the question– how do you reckon with a home built from a foundation of Black disciples and a white god? As Black people, what's the most civilized way to untangle love from sin?

Baldwin and Walker are asserting that the accumulation of white power symbols will not fill the void. What is needed is a queering of the way we practice community. The family structure must be one based on an ethic of love, not power. The Black Christian church is stifling. Its upholding of responsibility politics, heteronormative standards, and misogynoir are violent. The destructive inferiority complex interwoven with a hunger for white power warps Black love hence sabotaging the Black community.

The distortion of our worth based on the reality of our invisibility manifests itself in the ways we love each other. Baldwin writes “Black people, mainly, look down or look up but do not look at each other, not at you, and white people, mainly, look away.” He continues “The black man, as a historical entity and as a human being, has been hidden from him.” Love and empathy validate humanity and combat commodification. He continues to discuss the Black community saying “we sometimes achieved with each other a freedom that was close to love.” Freedom in that they understood each other's unique political and historical erasure.

Black people refuse to see each other because of a delusion of the rine and heart as Ralph Ellison put it. There are words like coon, sambo, uncle tom, and the mammy. Then there are words like hypocrite, charlatan, and trickster. Then there are subtler more gendered words like fast, stupid, ugly, and fruitcake. All these names capture in their way an effort rampant within African American culture to police and define each other based on minstrel archetypes.

Baldwin is turning this discussion on its head by asking what if all these binaries, sins, and materialism are rotting the Black community from the inside instead of validating our historical and/or political realness. It is not empowering us but isolating us from each other. We are policing each other and causing harm. Baldwin says “People always seem to band together in accordance to a principle that releases them from personal responsibility that has nothing to do with love.” In a culture of white supremacy accountability is the hard distorting mirror of Black invisibility.

Baldwin in his second letter creates new language to describe comparative freedom (a socio-political dissonance traditionally rendered in slave narratives) for the Modern Negro. “This endless struggle to achieve and reveal and confirm a human identity” culminates in an unshakeable authority (Baldwin, 1963). An authority that validates a person's humanity and in response sees everyone in the light of the human experience.

Hooks opens her novel All About Love writing “ to holding on, to knowing again that moment of rapture, of recognition where we can face one another as we really are, stripped of artifice and pretense, naked and not ashamed.”

The many loves of Celie's life enabled her to go through this spiritual journey of healing. I will note the instances where Walker’s narrative craft illuminates Celie’s racial socialization. Her reality as a dark-skinned Black female demonizes her in her community. A community within the historical clasp of chattel slavery and toiling in materialistic violence. Celie's revolution blooms a unique and personal lavender consciousness. Celie’s personhood was mutilated, then she molded her life in traumatized hands, to give birth to something beautiful.

Celie recounts the moment her mother asked about the paternity of her first child. “She ast me bout the first one. Whose is it? I say God’s. I don’t know no other man or what else to say” (p. 3). At this moment Celie speaks towards the mode of narration directly associating God with masculinity. And herself in God's image, invisible, and ignorant. Celie in this moment of pain cast the burden of her violation unto God because that is the only place she can spiritually hold the responsibility. That is the only way she is empowered to name her trauma. The construction of what god means to the narration articulates the character's growing consciousness.

DuBois writes in the Souls of Black Folk “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity” (p. 9). When communities perpetuate a person's inherent criminality and wrongness, said person is being socialized to worship ideals that hate them. Celie’s god hates her ugly, poor, black body. She feels this burn in the light of his worship. This is the smell of lavender over a fire that shakes the female daughter of slaves into consciousness.

Celie writes “I’m in the bed crying. Nettie she finally see the light of day, clear. Our new mammy she see it too. She in her room crying” (p. 8). The weight of Celie’s powerlessness falls upon her in godly light when her stepfather brings Albert to their porch and sells her hand in marriage. This blow to her humanity vibrates across the whole estate. Celie, Nettie, and their stepmother mourn their familiar powerlessness in the hands of the stepfather.

Hooks in All About Love paints a picture of a poor working-class Black mother saying “Her ethical values are eroded by the intensity of long and lack… Her life has been characterized by a lack of love” (p. 110). Celie at this point in the story is so overwhelmed with weakness and dispossession that she accepts defeat and ceases to believe life is livable under the burden of her reality.

Celie is drowning amok the shadow of sin. She is meek in God's masculine white hand. Nettie has just run away from her abusive stepfather and runs to Celie’s home with Albert. When Nettie arrives she is disheartened to find Celie suffering greatly. She asks her sister to fight to which Celie responds “But I don’t know how to fight. All I know to do is stay alive… If I was buried, I wouldn’t have to work. But I just say never mine, long as I can spell G- o - d I got somebody along” (p. 19).

Celie is not living but surviving for her companion, God. This connection to God and Nettie is her last surviving connection to humanity. The epistolary form here exemplifies Celie creating language to enable her survival. Celie overhears a conversation between Albert and his son about Albert’s last wife. “Harpo say, What wrong with my mammy? Mr. Blank say, Somebody kill her” (p. 30). This conversation asserts that a dead Black woman is viewed as a stain. A Black female being murdered by her Black male partner is a burden. This is the norm Celie is swallowing trapped on her plantation. Celie's predecessor is a bloody blemish on their shared family's memory, so what does that say for her raped, impoverished, and darker body?

Walker in In Search of our Mothers Gardens describes her ancestors as “Creators, who lived lives of spiritual waste, because they were so rich in spirituality—which is the basis of Art—that the strain of enduring their unused and unwanted talent drove them insane. Throwing away this spirituality was their pathetic attempt to lighten the soul to a weight their work-worn, sexually abused bodies could bear” (p. 340). Celie is writing through this spiritual Black hole, to uncover something more.

Celie tells Harpo that to remedy the discipline problem he has with his wife Sofia he should beat her. Harpo listens, so his relationship with Sofia becomes abusive. When Sofia confronts Celie about the harm she has caused to her own family Celie responds with remorse and says. “I say it cause I’m a fool, I say. I say it cause I’m jealous of you. I say it cause you do what I can’t… Fight” (p. 42). This is the first point where Celie vocalizes the shame she feels within the dialogue. It is also the first moment where honesty and accountability lead to restoration. Celie has caused a person she loves irreparable harm, so she confesses this fact to them and asks for forgiveness. Celie recognizes in Sofia a soulfulness that deserves reciprocation, not violence. She supports this sentiment in someone she loves, but doesn't hold enough love for herself to fight back in the abusive relationships she’s enduring.

Shortly after Celie and Sofia have a heart-to-heart Celie finds Harpo beaten and distraught on her porch steps. She is trying to help him understand that beating Sofia is not the right thing to do and says. “Mr. Blank marry me to take care of his children. I marry him cause my daddy made me. I don’t love Mr. Blank and he don’t love me. But you his wife, he say. Just like Sofia mine. The wife spose to mine” (p. 66). Celia at this moment is trying to illuminate to Harpo the fatal difference between real love and the drunken stupor of power rooted in ownership. His abusive father has shaped how Harpo values love and it is poisoning the whole family.

Hooks in All About Love says “We cannot know love if we remain unable to surrender our attachment to power, if any feeling of vulnerability strikes terror in our hearts” (p. 221). Harpo is dedicated to a principle of love defined by transaction as opposed to reciprocation. Celie is trying to tell him he is violently pushing away the love of his life. He is relegating the dynamic and strong woman he fell in love with to a prisoner of nuptials. Lovelessness torments and eventually tears apart Sofia and Harpo’s romantic relationship.

Sofia ends up leaving Harpo because he refuses to see her as a person, and continues to try to beat her into submission. The development of the relationship between Mary Agnes and Sofia exemplifies a queer family structure. Mary Agnes, formerly Squeak, was Harpo’s new redbone girlfriend after Sofia leaves him. Sofia and Squeak's first meeting is a violent confrontation where Sofia checks Squeak's unwarranted disrespect by socking her in the face. This moment could have been the jumping point for years of hostility between the woman but instead, it forges a strong bond of mutual respect that leads to familial love.

Sofia and Shug's defining character trait is their masculine determination to fight for themselves. When Squeak bucked against Sofia’s personhood she was punched back, and with that show of violence learned personally to respect Sofia. This strong sense of personhood leads to Sofia being arrested by the White supremacist police state in the south. Below is the moment Albert tells Mary Agnes what happened to Sofia ''No need to say more, Mr. Blank say. You know what happen if somebody slap Sofia. Squeak go white as a sheet. Naw, she say” (p. 90).

The Black female slave's rage is invisible. That is why Sofia especially is masculinized and viewed as an anomaly for her stubborn desire to defend herself. It is Squeak who must make a dehumanizing and traumatizing sacrifice to help free Sofia. The fact that Squeak had to endure sexual assault to release Sofia from jail is very telling of how a Black female's humanity is governed by Victorian morality and chattel slavery. Victorian morality subordinates the female slave to property. Squeak’s character arc began with her internalizing misogynoir to the point that Sofia had to physically correct her, and now Squeak is so moved by the injustice done to her family she puts herself in harm's way. She is violated in accordance with a culture of white supremacy while she is weaponizing her weakness to actualize a comrade's freedom. This moment reminds me of Nettie describing the intricacies and queerness of African polyamory. The friendship between oppressed women is something special and powerful. Sofia and Mary Agnes are sister wives with a spiritual bond that is beyond the bonds of a mutual lover.

The night Celie tells Shug the tragic circumstances that lead to her marriage to Albert is the night the couple first confesses their love to each other. Celie chooses to be vulnerable one night while Grady and Albert are gone. Shug learns that Celie was raped, impregnated, then sold off by her stepfather. Celie confesses that the only person to ever love her was Nettie, and she believes Nettie to be dead. Celie is consumed by sadness, loneliness, and shame. Shug sees her drowning in it and pulls her from the abyss with her confession of love.

Shug, motivated by love, finds Nettie’s letters amongst Albert's things and quickly shares them with Celie. After Nettie's letters are revealed Shug chooses to be vulnerable and confess her shame to Celie. “And when I come here, say Shug, I treated you so mean. Like you was a servant. And all because Albert married you. And I didn’t even want him for a husband” (p. 127). Shug apologized for weaponizing misogynoir against the woman she loved. She confesses to the harm she caused Celie rooted in the shame she felt surrounding her own sensuality. Before this point Shug held most of the power in their platonic relationship, now as they deepen their romantic bond it is beginning with a radical admission of truth.

The epistolary form mirrors this emotional and spiritual shift in their relationship because in the next letter to god Celie she mentions Albert by name. Up to this point, Albert in Celie's imagination is not a person but an authority figure to be unnamed and obeyed. Celie starts to view Albert as a deeply flawed individual as opposed to an unyielding force of power. This moment of rapture in Celie and Shug's romantic relationship caused a ripple in language.

Hooks articulates the reason why this truth was so vital to the cultivation of Celie and Shug's love story. “In large and small ways, we make choices based on a belief that honesty, openness, and personal integrity need to be expressed in public and private decisions… Our souls feel this lack when we act unethically, behaving in ways that diminish our spirits and dehumanize others” (p. 88). This quotation explains why Shug fell out of love with Albert after the revelation that he beat Celie. Their love could no longer be sustained amongst such parasitic violence.

Nettie writes to Celie in a letter “I remember one time you said your life made you feel so ashamed you couldn't even talk about it to God'' (p.136). Celie writes to God in a letter referring to Nettie and her children. “But it hard to think bout them. I feels shame. More than love, to tell the truth” (p. 154). After Celie reads the letter where Nettie reveals that their step-father was not their real father. She writes to God “You must be sleep” (p.183).

The next letter transforms the epistolary form. Celie ceases to write letters to God and begins to write letters to her sister. The revealing of family secrets helps Celie unravel her internalized shame. She can understand that the man that raped her was not her father. And this same man took advantage of her mentally ill mother after her father was killed by white supremacist. This truth frees Celie and Nettie alike. Celie accuses God of not listening to her meaning she will no longer be awaiting his salvation to make her life meaningful. Her life gains meaning through the abundance of love within it.

Up to this point God has been a bishop of shame and violence rooted within racial capitalism. Shug articulates a queer God motivated by an ethic of love as opposed to dominion. She paints her philosophy to Celia while they are cuddling in bed.

“God is inside you and inside everybody else. You come into the world with God. But only them that search for it inside find it. And sometimes it just manifest itself even if you not looking, or don’t know what you looking for. Trouble do it for most folks, I think. Sorrow, lord. Feeling like shit… She say, My first step from the old white man was trees. Then air, Then birds, Then other people… I think it pisses God off if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don’t notice it” (p. 203).

This gendered willfulness that can see the stinking masculine corruption everywhere is the manifestation of queer double consciousness. The internalization of hate is what makes Celie pray to a white male god that relies upon her shame and disenfranchisement. Shug is introducing radical love to Celie. Men project love into symbols of power, but women like Shug are love’s practitioners.

DuBois describes the veil and following shadow of racial determination as “ the ferment of his striving toward self-realization is to the strife of the white world like a wheel within a wheel: beyond the Veil are smaller but like problems of ideals, of leaders and the led, of serfdom, of poverty, of order and subordination, and, through all, the Veil of Race” (p. 65). This political tradition of subordination is an overgrowth of the antebellum period. Celie's art was able to escape and flourish within these historical circumstances because of the holy light of Black lesbian love.

Celie, with Shug's support, confronts Albert for the wrongs he has done against her and then leaves for the North. While they are away Albert falls into a deep depression. Sofia tells Celie years later when she returns after her stepfather's death. “Well, one night I walked up to tell Harpo something– and the two of them was just laying there on the bed fast asleep. Harpo holding his daddy in his arms. After that, I started to feel again for Harpo, Sofia say” (p. 231). Sofia loved Harpo and she was forced to leave him because he refused to see her as an autonomous person. His father is the same person who is the motivating reason why Harpo thought in the past it was his moral obligation as a man to control his wife as property. Harpo pulls Albert from the depression Celie banished him within for his abhorrent treatment of her. Sofia was touched by Harpo’s ability to care for his father, and that gave her room to forgive him. Love is malleable; we shape it in our bruised hands.

Towards the end of her family's journey in Africa as missionaries Nettie concludes that “not being tied to what God looks like, free’s us” (p. 264). At the news of her stepfather's death, Celie returns home to find immense beauty in the ruins of her undoing. When she's not living a disembodied life due to constant trauma she can see the beauty in things. She can listen to what surrounds her. Content sewing pants and lit up with lesbian love Celie becomes confident that she is not cursed, and maybe she even deserves the flush of happiness.

Walker says in, In Search of Our Mothers Gardens, “I notice that it is only when my mother is working in her flowers that she is radiant, almost to the point of being invisible—except as Creator: hand and eye. She is involved in work her soul must have. Ordering the universe in the image of her personal conception of Beauty” (p. 352). Celie has reached this comparative freedom with Shug by her side.

Albert and Celie fall in love for the first time when Shug has left them both. In their loneliness, grief, and codependency they fall in platonic love with each other. Celie is growing a budding sense of personhood and Shug opened her eyes to love and let the force of its queerness radicalize her life. But without the reassuring presence of romantic attention, Celie must hold steady her self-worth. And Albert alone due to the actions of his past is healing and relearning how to love. Albert and Celie learn to forgive themselves and each other. When Albert and Celie are having a conversation about love, he describes the soulfulness that both Shug and Sofia possess by saying. “You know Shug will fight, he say. Just like Sofia… What I love best bout Shug is what she been through, I say. When you look in Shug’s eyes you know she been where she been, seen what she seen, did what she did. And now she know” (p. 277). They are admiring qualities such as honesty, acceptance, and accountability.

Albert and Celie fall in love through listening to each other. Hooks says “Through giving to each other we learn how to experience mutuality. To heal the gender war rooted in struggles for power, women and men choose to make mutuality the basis of their bond, ensuring that each person’s growth matters and is nurtured” (p. 164). Sharing a mutuality that breaks the binaries of gender, that heals the violent tears in their relationship. They love Shug because they admire her shamelessness. She inspires them to love each other, and love themselves.

Hooks says “Love is an act, a participatory emotion.” (p. 165). Celie's letters to god narrate that queer love is a political action toward the liberation of community. That’s what we see through the interdependence, transformation, and queerness of the familial relationships in The Color Purple. Only through a Black queer lens was Celie’s family able to escape from their dungeon of sand, to shape god for themselves. From shaping god in your own divine image, an abundance of love can grow from shameful beginnings.

Baldwin, James. "The fire next time." James Baldwin: Collected Essays (1998): 291-349.

Du Bois, WE Burghardt. "The Souls Of Black Folk. pdf." (1903).

hooks, bell. All about love: New visions. Harper Perennial, 2001.

Howard-Pitney, David. “The Enduring Black Jeremiad: The American Jeremiad and Black Protest Rhetoric, from Frederick Douglass to W. E. B. Du Bois, 1841-1919.” American Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 3, 1986, pp. 481–92. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2712678. Accessed 10 Nov. 2022.

Walker, Alice. "In search of our mothers' gardens." New York (1972).

Walker, Alice. The color purple. Open Road Media, 2011.

The way that you've weaved together some of the most prolific writers about love is so beautiful. I am reading 'The Color Purple' for the first time and your analysis of Celie and spiritual development is powerful. It's allowing me to view the reading in a new way and I am even more excited to continue the journey of reading. I am also exploring my identity as a queer person, who is also helping my family move from pain/suffering to one of an ethic of love. The work that you've done is so integral to us moving forward as a people. Thank you for your contribution and your voice.